Born on March 9, 1947 in Poughkeepsie, New York, Mark Brian Ingraham lived life on his own terms, always in search of more expansive vistas and greater freedom.

Born on March 9, 1947 in Poughkeepsie, New York, Mark Brian Ingraham lived life on his own terms, always in search of more expansive vistas and greater freedom.

His story begins in Fishkill, New York where he was a born rebel. In kindergarten, the teacher sent him home because he was using an L-shaped building block as a gun; he insisted he was an outlaw from the wild, wild West. Through his teen years, Mark tore up that town, and the principal of his public high school—a stern man who also happened to be Mark’s father—kicked him out and enrolled him in the Peekskill Military Academy in the hopes that strict discipline would tame Mark’s rebel spirit. It didn’t work. The school shut down, and when no other school would take him, Mark earned his GED and used his quick mind and able hands to learn the skills he needed to become a skilled carpenter, a genius mechanic, and a master horticulturalist.

All of his life, Mark defied authority. When he was a teenager, he got a ticket for going under the posted speed limit on Main Street in Beacon, New York. An officer by the name of Hal Brilliant was escorting him out of town on a Harley, and Mark discovered that if he went slowly the officer’s bike would start to wobble. Slow enough, and Brilliant might go down. He did. Mark loved to tell this story.

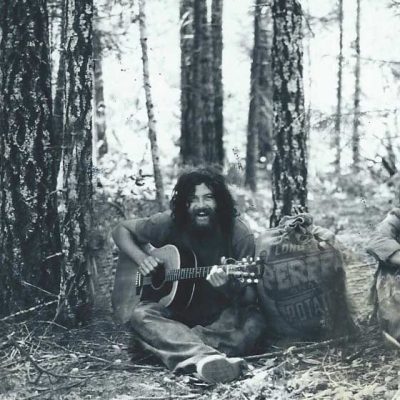

In July of 1969, just as all the other hippies were heading for Max Yasgur’s farm in Woodstock, 22-year-old Mark left New York state, headed out in the other direction, bound for Berkeley. After a year or so in the city, Mark knew he needed to get farther away, so he followed the path of some of his new California friends through the redwood forests and up into the Siskiyou National Forest where they shared a mining claim.

In July of 1969, just as all the other hippies were heading for Max Yasgur’s farm in Woodstock, 22-year-old Mark left New York state, headed out in the other direction, bound for Berkeley. After a year or so in the city, Mark knew he needed to get farther away, so he followed the path of some of his new California friends through the redwood forests and up into the Siskiyou National Forest where they shared a mining claim.

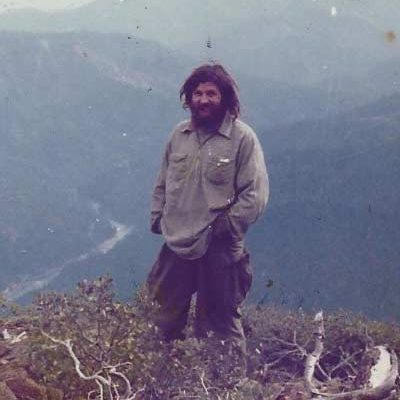

When Mark first moved to the wilderness in southern Oregon and started growing marijuana, he wrote to his sister about his new home: “The beauty took my breath away—as did the hills—and I was speechless (having no one to talk to). . . It is truly euphoric. Never, even up in the White Mountains, have I ever lived in such wilderness. Every day I have to cut enough wood, sometimes hauling it 1/2 mile because the supply is short, to keep warm and cook. If I ever cut myself with the axe or got attacked by a black bear no one would ever know. . . . It’s really very exciting knowing that you have yourself and yourself alone to keep you alive.”

From Oregon, Mark and his friends moved north, to the far northeast corner of Washington state, where they formed a sustaining and sustainable mountain community, living off the grid in beautiful cabins they built with their own hands, growing enough to support themselves and live simply. But as government surveillance technology changed, so too did the hippies’ methods, and in the late eighties, Mark and three comrades formed an alliance with some farmers at the foot of the hill. The plan was to grow the pot between the rows of corn. For four years, this worked, but in the fall of 1992, Mark was arrested in what was touted as the biggest outdoor growing bust Washington state had ever seen. The story was all over the papers: rows and rows of mature female plants, high-grade Indigo hybrids, covered with green, purple-tinged, hairy buds.

Mark, a non-violent offender, ever loyal, refused to inform on any of his partners, refused to cooperate with the authorities in any way, and he was sentenced to all ten years of a mandatory minimum in a Conspiracy to Manufacture, Distribute, and Possess with Intent to Distribute over 1,000 Marijuana Plants. Mark didn’t need predictability, structure, or any institution—but he desperately needed his freedom. For twenty-five years he had lived on the tops of mountains in hand-hewn cabins with fresh air, bright sun, and no fences. He did not survive prison. Mark was only half way through his sentence when he died in Lexington, Kentucky on August 7, 1997.

Mark, a non-violent offender, ever loyal, refused to inform on any of his partners, refused to cooperate with the authorities in any way, and he was sentenced to all ten years of a mandatory minimum in a Conspiracy to Manufacture, Distribute, and Possess with Intent to Distribute over 1,000 Marijuana Plants. Mark didn’t need predictability, structure, or any institution—but he desperately needed his freedom. For twenty-five years he had lived on the tops of mountains in hand-hewn cabins with fresh air, bright sun, and no fences. He did not survive prison. Mark was only half way through his sentence when he died in Lexington, Kentucky on August 7, 1997.

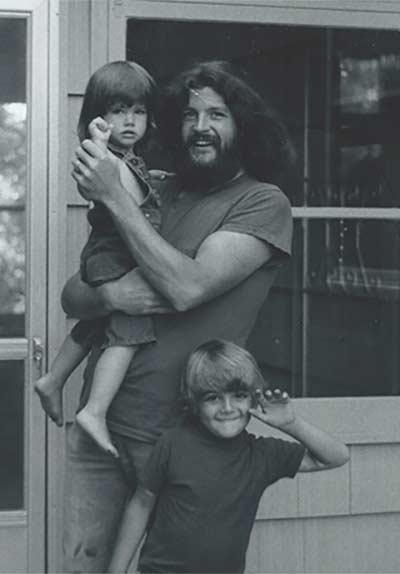

Mark was known by many names—Ingraham, Markie Boy, Uncle Mark—but all who knew and love him agree on one thing: If Mark was there, it was a party.

And all who knew and love him miss Uncle Mark still—and forever—and celebrate his rebel spirit.